Short answer YES. Long answer, YES. Long vilified as a cause of heart disease, saturated fat is now considered beneficial in many mainstream circles. But old habits die hard, and one researcher in New Zealand appears to have spun the anti-sat-fat and anti-butter movement up to new and uncharted territory.

Short answer YES. Long answer, YES. Long vilified as a cause of heart disease, saturated fat is now considered beneficial in many mainstream circles. But old habits die hard, and one researcher in New Zealand appears to have spun the anti-sat-fat and anti-butter movement up to new and uncharted territory.

A regular blog reader, James A., of New Zealand wrote us:

Rod Jackson, a professor of epidemiology at Auckland University, launched a strident attack against butter and other saturated fats in the New Zealand Listener. This is a respected magazine which gives Jackson’s attack considerable weight in this country. Butter is his particular target as he says butter consumption is increasing again from an average consumption per person of 7kg to now being 20kg per person. This will have, according to him, dire consequences. He goes on to say the only reason that we are not yet seeing a rise in heart disease due to the increased butter consumption is because people are taking their statins!

He does not refer to any research which supports his views. [emphasis ours]

The article resulted in a mass of letters in the February 4-10 2017 edition just out. The editor has responded in a note saying Harvard’s School of Public Health is unambiguous about butter’s downside and that saturated fat is well-established risk for cardiovascular disease. I have not been able to find that research.

Among your other blogs I have followed, enjoyed and lived by your Grand Unified Theory of Fat. One unintended consequence is that both me my wife and I lost weight when we switched to more fat and less carbohydrate.

I would like to present to the Listener and Rod Jackson research on which you have relied to debunk the antagonism towards fats and in particular saturated fats. Could you send me references to me? Even better would you like to respond to the article in the Listener? I could scan it or get the editor to send you an online copy.

Any response from you would be much appreciated.

We wrote a letter back, and James has passed it along to the New Zealand Listener, but given their response to their reader’s protests, listening may not be one of their strongest points.

The researcher , Rod Jackson, is an epidemiologist, not a medical doctor. He mines databases (epidemiologies), and publishes his conclusions. Various topics include the roles of sleepiness in car crashes, effects of alcohol on heart disease and on falls, and so on.

We Don’t Like Epidemiological Studies and Stat Packages

We don’t like them even when we agree with the results. The reason is this: armed with a statistics package, and with enough control of variables and selected outcomes, almost any result is possible. It is often the case that there is a desired result. Drug companies want their new drug to work, and do not want serious side effects. We are not trying to intimate that epidemiological research is inherently biased, but even with serious efforts at neutrality, if is quite hard to achieve objectivity. Subjective judgments invariably creeps in. Should this data even be included? How should the outcome be presented? The worst compared to the best, or the worst compared to the average? It goes on and on.

Others have weighed in.

There are lies, damn lies, and statistics -Benjamin Disraeli

With four parameters I can fit an elephant, and with five I can make him wiggle his trunk. -John Von Neumann

My (Davis) own experiences in applying statistical analysis to the stock market was, how should I put this, rather expensive.

Especially suspect are studies of large groups of people, which produce minor differences in outcomes. For example, whole grain versus refined grain is said to reduce 10% reduction in colon cancer. It may well, but 10% isn’t much of an improvement. Was industry funding any of this?

The older epidemiological evidence typically presents evidence that saturated fat is bad. The new epidemiological research, say over the last five years, generally concludes that saturated fat is either harmless or good for you. So, either humans drastically changed the way they deal with fat, or something changed in how the research was done, or perhaps how it was funded.

So What Do We Trust?

There are other ways to look at things. For example, if statistics say such and such causes heart disease, there has to be a reason for this. Often we do not know why, but if we do know, we would expect the biology to mirror the statistics.

Pathways

There is a reason for everything, but living creatures are unbelievably complex and much is not understood. However, quite a lot is understood. Inflammation is associated with cancer. That is a statistical result. However, if one zooms down to the molecular level, there are very direct reasons why an inflammatory environment would interfere with accurate cellular reproduction and hence make cancerous mutations more likely. Here, what is known at the molecular, biological level strongly supports the statistics.

For saturated fat, we are lacking both the statistical evidence as well as the biological. Studies that implicate saturated fat tend to be old and often include trans fat. Trans fat is well known to be dangerous. Here is an easy way to get a “saturated fat is bad” result, and was widely applied

As mentioned, the more recent epidemiological papers tend to exonerate saturated fat. What does the body do with fat? A lot is known here. There are two major uses: metabolism and cell-wall construction.

A little chemistry: a fat is a string of carbon atoms. Lengths vary and tend to be in the range 8-20 give or take. Stuck to all the carbon atoms are hydrogen molecules. In a saturated fat, there will be two hydrogen atoms stuck to each carbon. This is the most a carbon atom can hold, hence the term saturated—it is saturated with hydrogen atoms. In an unsaturated fat, one (mono) or more (poly) of the carbon atoms is missing a hydrogen atom. When this occurs, the carbon chain develops a kink. Monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats are in this category. The straight saturated fat chains stack better and take up less space. For this reason, saturated fats tend to be solid at room temperature.

To convert a fat into energy, cellular processes pluck a pair of carbon atoms from a fat chain and feed them to our energy-generating mitochondria. As the cell proceeds to snip off more and more pairs of carbon atoms, it may come to a kink, or it may come to the end and find there is only one left. Of course, it has other processed that can work around these “defects,” but the path of least resistance is to burn fat chains with even numbers of carbon atoms, and no kinks. This well describes saturated fat. So from an energy burning perspective, saturated fact would seem to be the preferred fuel. Hard to see any connection with heart attacks here.

The other major use is cell wall construction. This is different. Here the body is very picky, requiring very exact fat chains. It could just wait for the right one to float by in the bloodstream, but it will usually snip and paste and gin up whatever it needs. In this sense, it doesn’t matter which fats, but as with the metabolism, saturated fats are the best raw materials for this assembly operation. This is where the omega-3 and omega-6 fats come in. The body needs these but can’t make them, and so must wait and snatch one out of the blood stream.

For these two major uses to which fat is put, saturated fat appears to be the one with the fewest complication. Hard to translate this to heart disease by looking at the pathways.

Trans fat is a major exception. It’s man made and the body doesn’t know what to do with it. It uses it in places it shouldn’t, compromising cell-wall integrity and thereby promoting cancer. (Beware, “no trans fat” means less than a half gram. Is this safe? Unlikely.)

Raw Data

Suppose data is simply collected, but without any particular agenda. Data collected on a drug in a trial wouldn’t meet this criterion. The drug companies have an agenda.

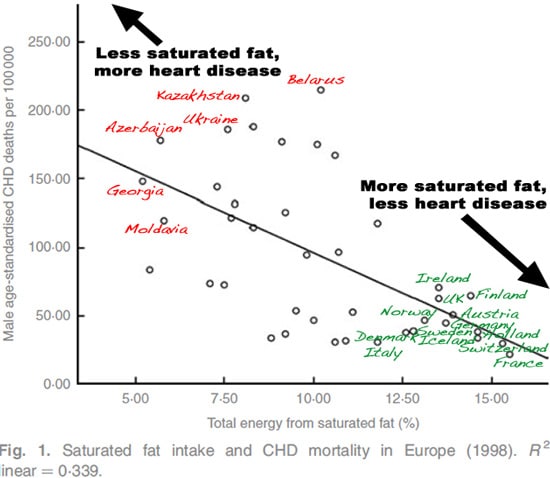

But suppose someone undertook to examine the differences between countries. One can find all sorts of information by country. Rate of heart disease, for instance would be found in one study. Food consumption in another. A country-by-country comparison of saturated fat versus heart disease can be found here. Here is their plot.

You do not need any statistical analysis to see that the more saturated fat consumed, the less heart disease. It jumps out at you. Are there confounding factors? Smoking? Alcohol? No doubt, but raw data that tells a strong story really needs a thoroughly convincing counter story to rebut it. I don’t think any statistical analysis would convince us that what is staring us plainly in the face is incorrect.

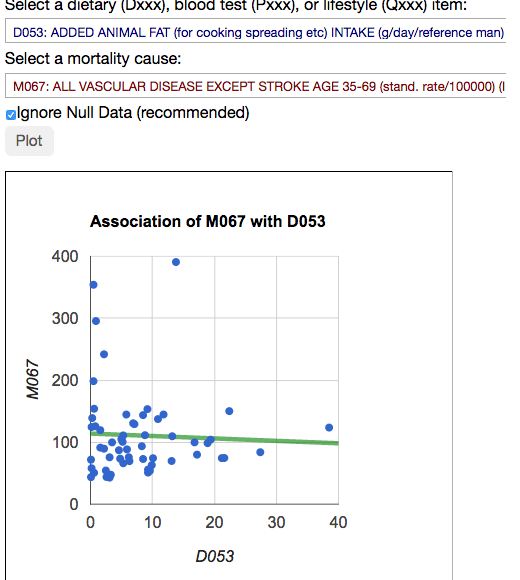

Another excellent example is the raw data used in the China Study. As many of you know, there is a book called “The China Study” which asserts that all animal product in unequivocally bad. The actual raw data says the complete opposite. More saturated fat, less heart disease, more animal fat, lower mortality.

Here is a plot of the raw data using our do-it-yourself China Study, found here.

Here are two cases of raw data with a compelling message: saturated fat is good for you.

Clinical Settings

Dr. Mike could be called a lifestyle physician. For the last 20 years, he has treated several thousand people, made measurements, recommended dietary and exercise modifications, and in most cases, has been able to follow the impact of the changes with more tests—an iterative process really. People who follow the protocols experience far lower levels of the chronic diseases‑heart disease, cancer, diabetes, dementia. In most cases, patients were able to reverse these diseases.

So how did he do this?

Dr. Mike is a data freak. He collects data (blood tests, body composition, arterial calcium, etc.), proposes changes, and looks at the resulting data. Everyone is different. However, increased dietary fat, saturated or otherwise, improved health. Sugar and starch, though, stood out as major health culprits. Had it been otherwise, Dr. Mike would have recommended accordingly. Way back in the 90s, when saturated fat was spoken of in hushed tones, we had Dr. Mike saying that for most people, the best diet is 1) clean high quality food—organic vegetables and grass fed meat 2) cut out the sugar and starch 3) Don’t worry about fat. He criticized heavily for this.

However, people got well, and stayed well. This is hard to argue with.

. Don’t worry about saturated fat.

Saturated fat isn’t the issue. The real issue is quality. How clean is the meat or fish you are eating? Were antibiotic and feedlot practices involved, or was the meat grass fed? Was the fish farmed or caught wild? As far as processed meat goes, beware.

Excellent article, Dr Mike. Thank you. I would love a future article from you on dietary fat, specifically saturated fat, and breast cancer. I believe there is a huge amount of confusion and misguided advice about this out there. I have read that certain types of fat cells could produce hormones after menopause, but eating butter would not by itself raise blood levels of estrogen….or am I wrong?

Also, something else that could skew the studies (Jeff Volek and Ron Rosedale among other constantly emphasize this point) is that high saturated fat (or possibly any fat) in the context of a high-carb, eat-all-the-time-chronically-elevated-insulin diet may be bad in that context, although such a diet will lead to problems even without the fat.

Hi Vincent,

This idea began long ago as a rescue mission for the researchers who had spent their lives on the sat fat hypothesis. The theory behind it came from believing the role of glycation and lipid oxidation were linked. Time has shown this is not as big a factor as the simple calorie overload of the combination of starch/sugar/insulin/fats(any kind). After the starch/insulin link became clearer and more clearly dominant, in those insulin resistant, the variables that matter most are calorie distribution throughout the day – “Eat for what you are going to do rather than what you have done” – and then, and only then, on actual caloric load. To the simple take: is it worse to eat starch and sat fat or just sat fat? The simple answer is the combo is worse. The danger is thinking: well, I won’t eat starch and sat fat at the same meal so it is OK to have each. For the truly insulin insensitive this just does not work. Big breakfast, smaller lunch, little dinner works for everyone. Dr. Mike